I’m not an American, so I cannot sign a petition to expand bike lane infrastructure and protection in Evanston. The campaigner looked disappointed, but less about the everyday life of the sovereignty border and more about not having enough signatures. We talked for a bit, though; I told her I am a researcher of spatial planning, and I had planned and supervised some projects for my own research. So we started listing every biking problems in Chicagoland: no bollards, not enough bollards, no bridge, bad bridge, no painting, why only painting. We both felt unsafe biking here, and I told her I’d never been happier than biking in the Alps. My mountain bike hanging by the cable car up to the mountain. I fell to one of the Aare river subsidiaries, I cried — while laughing.

It took a while, but then I finally figured out why I am rarely comfortable with urban biking so much — the roads. Specifically asphalt roads. The roads, the very thing that reminds of plantations. The asphalt, the construction of roads, the heat that it breathes visibly when it’s 35 degrees Celcius. The coals that are in my step. Especially highway. Only a few things in this world that I can passionately say “hate” with such immense disgust. The kind of hatred that reminds me of Ted Kadzynsky whenever I’m in the car on a highway. I hate anything that bares me from my naked feet, like how my grandmother taught me how to feel the Earth’s pulse.

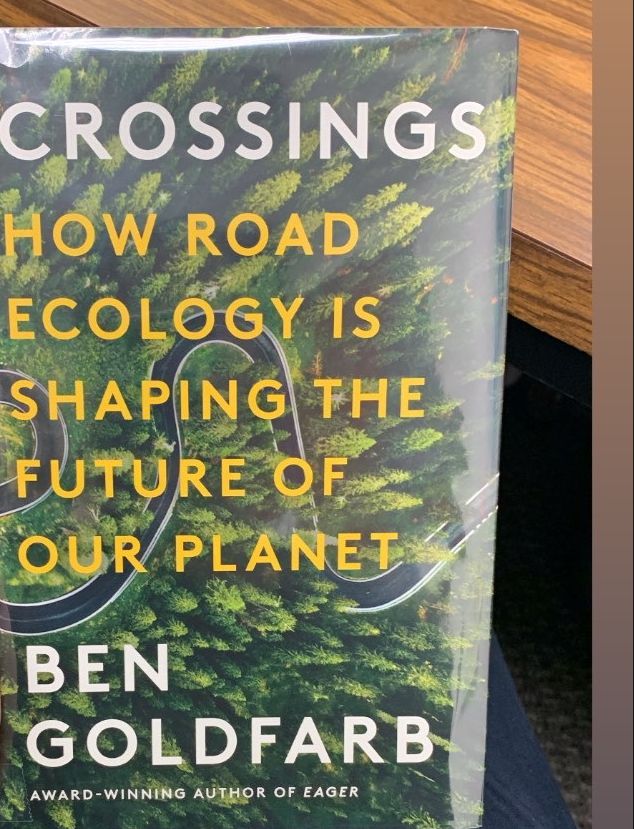

After seeing the impact of the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, Ben Goldfarb in Crossings (2023) writes that roads are not just a peak of infrastructure but “a distinct disease” (p.7). In the most stunning part of the book, Goldfarb emphasizes how road designs perpetuate racism and racialization of people of color, furthering the demarcation of what W.E.B DuBois calls the “color line.” Redlining is not just a term in finance but has a concrete mechanism in which roads are quite literally lining who “gets “deserves” better credit scores than others. Most working-class people of color in the US live near freeways or highways, where food deserts occur. I always noticed this about Chicagoland (the south & west sides in particular), but I did not quite understand the magnitude because I lived in the bubble of Northwestern’s Evanston. Not until I stayed in Fort Dupont, DC, and biked every day to Capitol Hill on a designated and protected bike lane in a highway did I finally understand how highways support the racial segregation persistent in the Anacostia River.

In his book, Goldfarb specifies how highways can serve as a tool for white supremacy by supporting housing and sanitary segregation during the Jim Crow era and deciding who belongs to the United States of America (p.276). Urban highways as we know it then become necropolitics, where Brown and Black communities in the US are more likely to suffer from asthma and diesel particulate matter (combustion from asphalts), which can also lead to cancer in the long term, than any other groups. Highways create urban heat islands, suffocating residents and ecosystems around them. And still, no matter how many roads are built, they’re never enough for some reason. And indeed, cars only exacerbate such a “need” if not totally supported. In the US, more than 40,000 people die yearly in car accidents. Lives are expendable, but not highways, interstates, and freeways — whose creation has greatly contributed to soil depletion and lead contamination in urban groundwater.

But how about roads in the rural areas? Just like American planners in the ’60s, Dutch colonizers and present-day rogue Indonesian politicians never stop claiming roads as a symbol of development, access, and modernity. Discussing road networks during the peak of timber production in Indonesia, one state planner told me, “It’s good that roads are built through the forests in Kalimantan; otherwise, what would you do? Continuing the dayaks way?” He laughed, and it took a whole human in me not to retort to violence. Dayak is a colonial (and later colloquial and sometimes derogatory) term used to describe various indigenous communities and subgroups in Borneo. People in transmigration still use Dayak to refer to “lazy natives” who “refuse the wealth from palm oil.” In 2018, a Dutch historian contended that the pain and devastation from slavery had been “exaggerated” and should be “put in context” because, after all, the Dutch colonizers “built roads” for Surinameses and Indonesians.

For better or worse, roads create their own ecosystem (thus, the invention of a subdiscipline called road ecology). It is not just humans (through any variables and means contained under capitalism) who change the ecosystems once roads are implanted, but roads create and alter forms of lives surrounding them and beyond. I have spent the last 7 years thinking and talking about palm oil plantations and roads have been grossly ignored to understand the health problems suffered by plantation communities afflicted by the spatial gridlock. I lost count of how many times I received threats and harassment by plantation security officers (mostly cops; wouldn’t you be surprised!) who banned me from wandering around plantations. Sometimes, they also made it difficult for (unionized) workers to take someone around the estate. “This is not for the public,” a police officer barked at me. I reasoned it didn’t matter because I wanted to take a shortcut to my host’s house. “No, this road belongs to companies. Not anybody else.” Per Indonesia’s domein verklaring, no one except the state and individuals can own land. But Land Use Rights poisons many’s minds to think that land on plantations is a corporate jurisdiction.

Main roads in palm oil plantations are a hit or miss: sometimes they’re crisp, and sometimes only God knows how the business can last for over a century with road qualities that only Moses can get through by splitting them into two. In most areas, rain will absolutely obliterate the roads. Every monsoon season, there will be viral videos about the hardships of teachers in remote areas not being paid enough to go through mud waves and teach 2nd-grade Mathematics to 5th graders in plantation schools. Plantation roads and freeways surround workers, smallholders, indigenous people, and villagers like a sleeping phyton. Yet, the good roads are only the outside; entering plantations is a horrible business. The roads are not made for or based on safety, but commodity: the workers and the fresh fruit bunch (the palm oil fruits). Two of my informants died from vehicle accidents on plantation roads. Lives, once again, are expendable for roads.

Ugly, deadly roads are designed, not out of nowhere, and neither it’s just a matter of bad planning and under-funding. The spatial power of plantations subjugates communities using roads to create political divides between workers, estate managers, and surrounding afflicted communities. The roads further plantation communities from access; economists found low capital mobility in palm oil plantations. It’s a nightmarish, endless fun house where you’re trapped, but it’s neither fun, a mere nightmare, nor a house.

What kind of lives are built by roads, exactly? In his poem (Still Another Day), Neruda reminds us: if when I want/to tell the story of my life/it’s the land I talk about./This is the land/It grows in your blood/and you grow./If it dies in your blood/you die out. Roads dry out blood from land and from people, too. Roads are alien to me because they are of landed material but feel otherworldly, not in a good way. I drove 35 miles to my fieldwork, and on the highway, a local police station hung a banner: “Please don’t get into a car accident; the hospital is very far away.” Nothing but palm oil plantations for the next 10 miles. The cop might be right: this road doesn’t belong to me.

Leave a comment