One deep breath, two deep breaths, and fever dreams ever since. I forgot how to deal with plantations. Other traumas did that to my body. She asked me a very simple question, “Is there any way we can plant palm oil without these…. toxins?” The second day of this labor safety and occupational hazard workshop. The pause after her penultimate word has no end, tangled and rooted like palm oil’s roots. I shook my head, I do not know. Maybe I will never do.

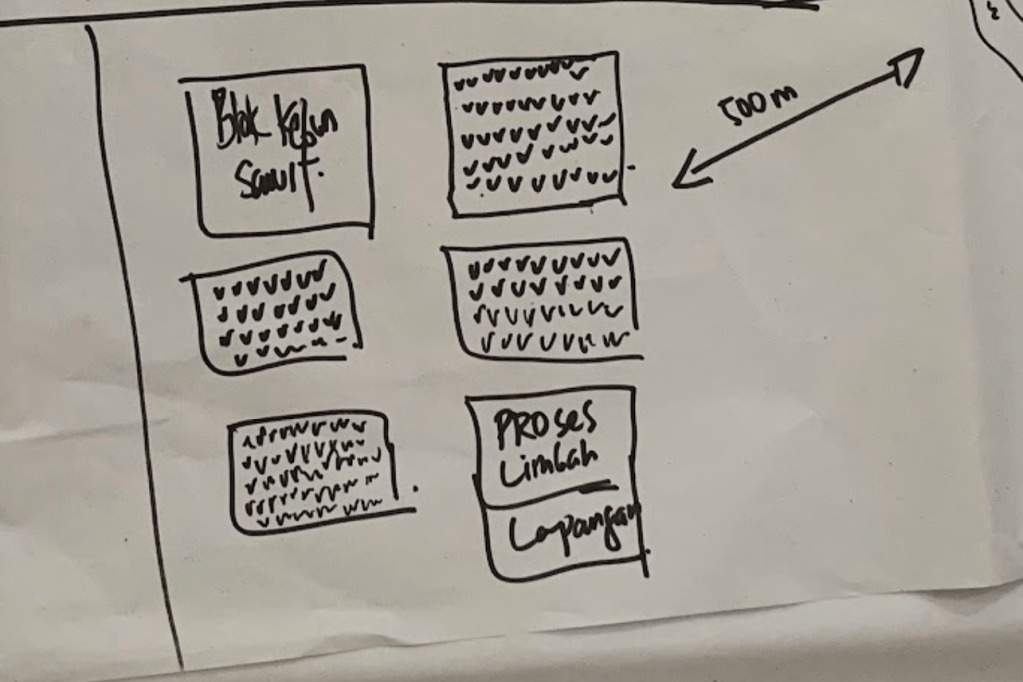

The KCl fertilizers that my nostrils had exhumed for a while. The 16-ltr kep* of pesticides. I no longer have no idea what they mean. I know how to burn plantations to the ground, I never know how to fix them. “It’s always been a system,” argued Rb. I nod helplessly — plantations are more than a machine (what is a machine, anyway? Who operates the machine? Who built the machine? What makes a machine machines?).

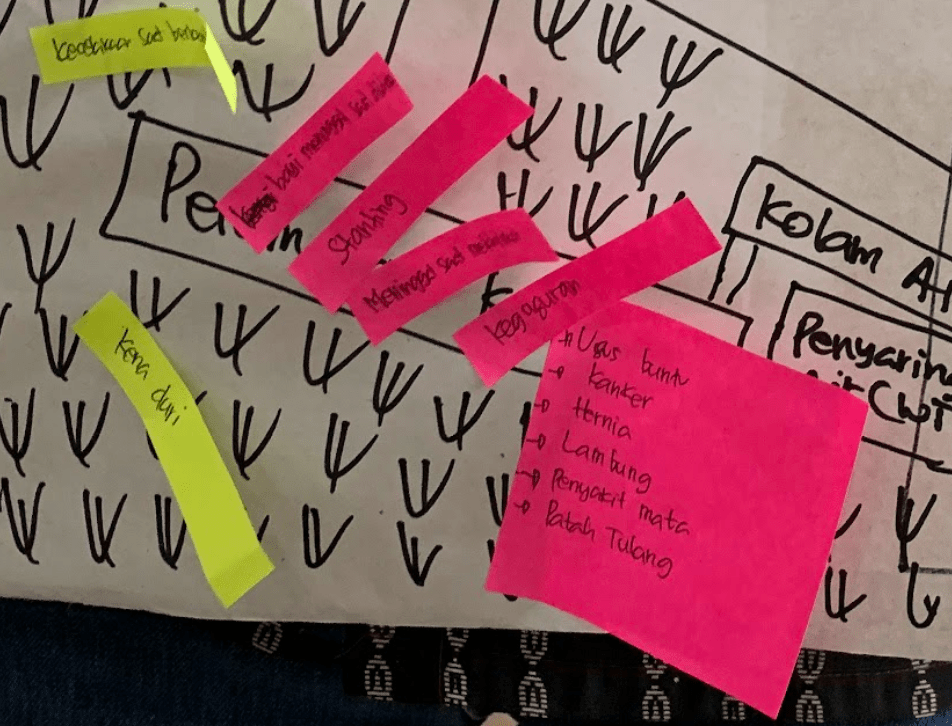

Nature as one’s inorganic body — or there is nothing unnatural about New York City, per David Harvey — finds its most gruesome manifestation in intoxicated bodies waiting for cancers and other long-term illness. I jotted down my field-note on that day: is there any labor that is not debilitating? The inorganic for laborers is the subjugation under this corporeality: as plantations inhale the toxins, so do the workers and farmers — yet they are external to each other. Alienated. The political unconscious still remains, though: the absence of their answer to “what’s after plantations?”

“I do not know what Gramoxone contains,” she told me again. I do. It contains paraquat, an organic compound used for herbicide, non-selective weed killing one. Corrosive to aluminium. Carcinogenic. So lethal for humans, many farmers used that for suicide — when they could no longer take the debt, or when they became too ill from the toxin exposure, they walked into their field, drank that dark-colored liquid. Among the leading cause of Parkinson’s disease in rural populations.

Usually it goes like this: farmers or plantation workers get exposed to highly poisonous pesticides and herbicides, produced by this agrobusiness company. For many farmers, they are in debt just to obtain the toxins because the subsidies have been cut unless you are part of plantation/farming corporations. Then they get sick, and in debt. Because they couldn’t afford to get medical treatments and medicines produced from the very same company that gave them the illness in the first time. Then the statistics of how badly our country treats farmers and farming workers ensues. Endless Suicide Hotlines. If any. Because who gave a fuck about farmers?

“I know someone who got cancer—“

“I know someone who got miscarriage in the plantations—“

“I know someone who died—“

“I know someone who was—“

Truly, who gives a fuck to the dictum that thou shall not fuck around with those who make your food happen.

“I know someone who—“

***

In May, she lost her baby. Plantations tore her with their spiky teeth, roughly. Palm oil blooms every week. It’s always Spring in the plantations. Blades. A jaw of abyss.**

*kep is what workers call spraying containers for liquid fertilizers or pesticides/herbicides — or “toxin”

**rendition from Mary Oliver’s Spring (1990) and Spring (2004).

Leave a comment