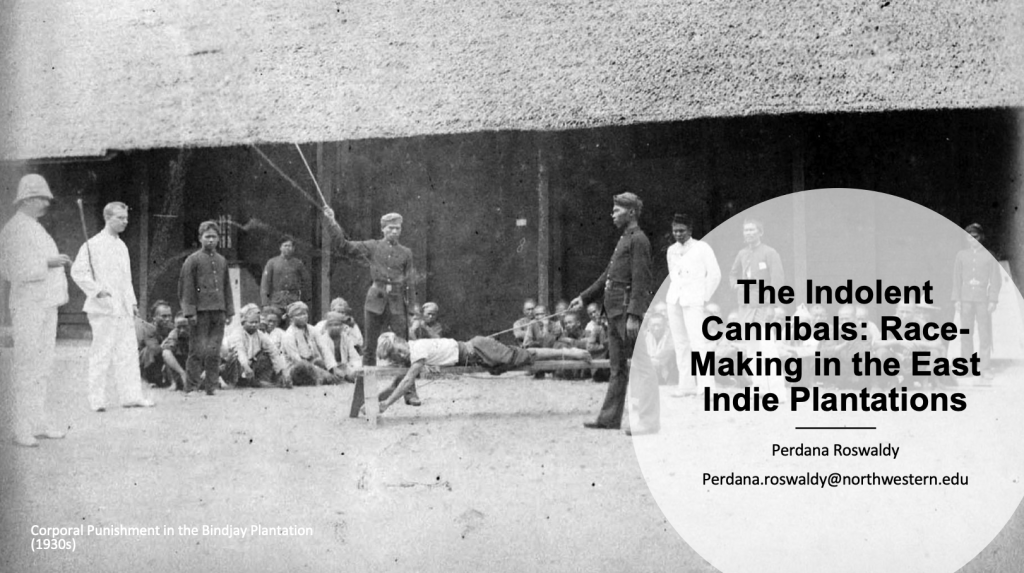

I’m in my feelings these days, reading these Dutch colonial fictions. It is funny to say “colonial fiction” because this phrase sounds repetitive; you can replace colonial with fictional and everything will start making sense.* Race, skin pigmentation, laziness, and the cannibals — all the fictional constructions of plantations under their colonial ruins.

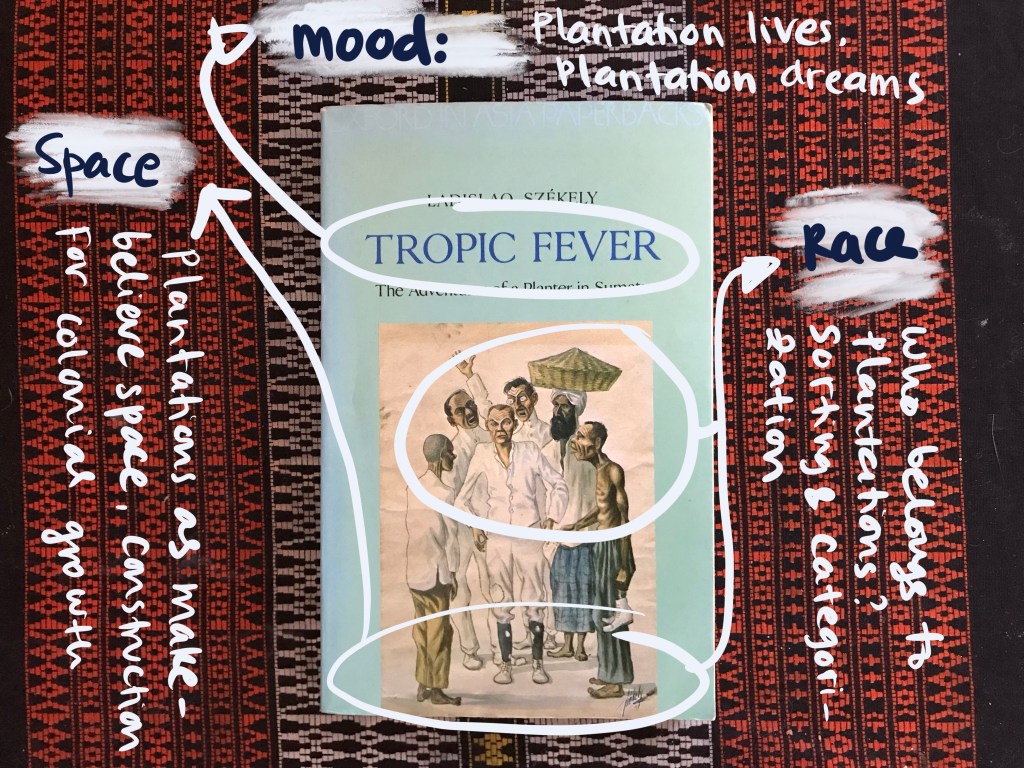

One novel haunts me though: Tropic Fever by Ladislao Szkely, a Hungarian planter in Deli turned a novelist. His novel is a semi-authobiographical, describing his life as a plantation overseer in a tobacco plantation. All of the miseries started not with the falling trees and the death of tigers, but tropenkoller or tropic fever; a fever that is too mysterious to understand, the heat that is too unbearable for the Whites.

This scene unsettles me greatly: the rape, and the murder, of Ms. Hopkinson — it is not vivid or anything, so it is not something that is triggering. Rather, the perpetrator Badar Singh is the one who occupies my mind, a Tamil chauffer for the Hopkinson family — the American planter family from Honolulu. There is a paragraph that describes Singh with an 101 orientalist narrative: that he’s a tall, muscly man; where he comes from, a Brown man captures tigers with spears not guns, his beard is black as night, his headwrap hides his long curly slender hair. Ms. Hopkinson, or the mem, is a blonde white woman, with an exceptional beauty: round eyes straight from the finest painting.

When Mr. Hopkinson finally found out what happened, he was too stunned to understand what happened. Singh also didn’t say a word. Both men sat down idly in the veranda before the coolies and the servants understood what was going on. Mr. Hopkinson then went back to the US, with uncurable sickness. The fate of Badar Singh, however, is sufficiently encapsulated in five words, way less than the description of his body: “Badar Singh later was hanged.”

I was not sure what was so peculiar about how the novel portrayed Badar Singh that made me enraged — not that I have a sympathy for a rapist and a woman beater. But what did white men do? Why did Mr. Hopkinson just sat down in the veranda? Why women do not even have any dialogue here except when the brown women said, “Yes, Sir, here’s your beer”? I was so perplexed. And to think that this novel, like many colonial novels at that time, was hailed as a sympathetic portrayal of the indigenous population and the coolies in the East Indie.

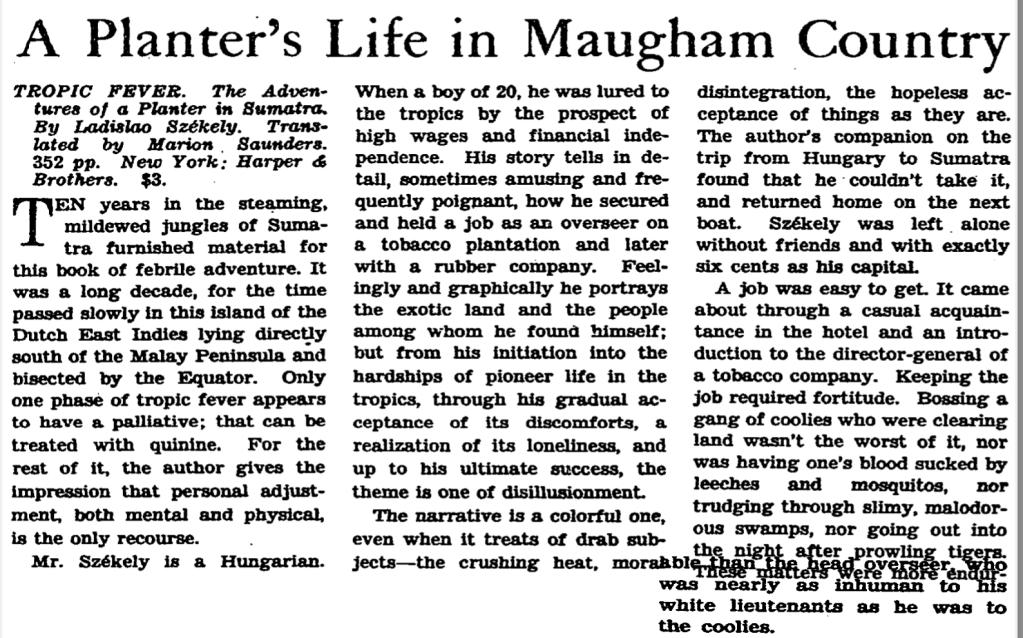

The New York Times review of Tropic Fever by Edward Frank Allen, on February 7, 1937. No mention of colonialism. But he describes the East Indie as an exotic place for an adventure-thirst man.

“I cannot articulate my feeling,” I texted Nike. “But all I know there is inexplicable & flaming anger in me after reading that scene.” Brown women are disposable, heartless creatures who would just feel grateful for men’s beating. All that matters, and the only tragedy is the fall of white lives — either from the heat or the danger of a tiger-hunting Black man. Plantations are indeed nothing but a fever dream that comes true to afflict those who desperately cling onto their dreams of tomorrow, sacrificing their Brown and Black back and tears.

* Thank you so much for the brilliant Prince Grace who attended my Race & Society presentation for this commentary (colonial/fictional)!

Leave a comment